-

About

Author: Lily Tomson (Senior Research Associate, IF, Jesus College; Departmental Fellow, Finance for Systemic Change, Department of Land Economy, University of Cambridge)

Lead Research Assistants: Madeleine Taylor and Mia (Lakshmi) Sannapureddy (Finance for Systemic Change, Department of Land Economy, University of Cambridge)

Acknowledgements: Many thanks to Brett Olson (GFANZ), Elena Vydrine (IIGCC), Angeline Robertson (Stand.Earth Research Group), Dr Belinda Bell and Ellen Quigley (Finance for Systemic Change, Department of Land Economy, University of Cambridge)

Publication date: October 2024

Finance for Systemic Change

Finance for Systemic Change at the University of Cambridge is a research centre that aims to undertake and deploy academic research to mitigate systemic risks by working to change the practices of asset owners and other systemic actors and by seeding the elements of a future equitable financial system. Our work is based on an evolving body of academic evidence and entails a fundamental reimagining of the relationships among investors and the economy, society, and the natural world. In particular, our work as confidantes and challengers to some of the world’s largest asset owners presents a catalytic opportunity to mitigate the global catastrophic risks we face and to open the door to a more equitable future.

The Intellectual Forum

The Intellectual Forum is a centre based at Jesus College, Cambridge that provides a space for multidisciplinary research and discussion amongst academics, students, industry leaders, policymakers, and members of the global public.

Disclaimer

This report is intended only for informational and educational purposes. It is not intended to be, and should not be relied upon as being, legal, financial, investment, tax, accounting, regulatory business, or other professional advice. This report is also not intended to be, and should not be relied upon as being, a recommendation or endorsement of any investment strategy or approach, or any entity, financial product, or index. Finance for Systemic Change does not provide investment or any other professional advice and is not liable for any decision you make.

Finance for Systemic Change does not represent or warrant that this report is accurate, complete, correct, up-to-date or suitable for any specific purpose, and none of Finance for Systemic Change or its employees or staff shall have any direct or indirect liability arising from, or relating to, the use of this report or its contents.

-

Table of Contents

-

Introduction

As academics and researchers working on sustainable finance, we noticed the lack of in-depth research into the intersection of fixed income, index construction, and climate change.1 Compared to topics such as green and sustainability-linked bonds, which have received significant attention on the conference circuit and in academia,2 the climate impacts of index construction have spent comparatively less time in the spotlight. However, academic research suggests that changes to existing indices have considerable potential to shape outcomes in the real economy.3

We aim to provide major global asset owners with an overview of how their peers think about the intersections among the rise of index investing, the unfolding climate crisis, and the role of corporate bonds.4 This research explores the gaps between the financial risk-based approaches that have long been used by bond investors and the systemic risk approach of asset owners who think of themselves as Universal Owners – large asset owners with diversified portfolios and therefore a vested interest in the health of the overall economy.

In the first section, we explore how asset owners are grappling with climate in relation to their corporate bond portfolios, and specifically the extent to which asset owner climate commitments include corporate bonds. We look at asset owners’ adoption of fossil fuel exclusions and interim net zero targets. Interim (or near-term) emissions targets set out tangible steps an asset owner needs to take to reach net zero. We focus on these targets, as opposed to targets with a 2040 or 2050 date, as they are often both more specific than a long-term net zero target and more closely related to specific actions the asset owner is taking in the present.

In the second section, we turn to climate benchmark use. For readers who are unfamiliar with concepts such as benchmarks and indices, we have created a parallel guide that can be found here. We present five key challenges asset owners are facing, and the routes they have taken to overcome these. We consider the importance of having internal alignment on the purpose of benchmarks, the potential role of indices in corporate bond engagement, the role of asset owners in innovating new climate indices, ways that smaller asset owners have developed index solutions, and how all asset owners have tackled tracking error and data challenges. Throughout this section, the importance of asset owners learning from the experience of peers shines through. A summary of key insights from both sections can be found below.

-

Insights

In exploring how asset owners view the relationship between corporate bonds, climate considerations, and index investing, this report identifies several core insights for asset owners:

- Asset owners are increasingly including corporate bonds within the scope of their climate commitments.

- Our data show a growing trend among asset owners to apply fossil fuel exclusions to corporate bond holdings. Notably, all asset owners who have announced fossil fuel exclusion policies since 2022 have included corporate bonds.

- Combining revenue thresholds with power generation metrics is the most popular approach defining fossil fuel exclusion commitments. This method prevents diversified but highly polluting fossil fuel companies from being overlooked.

- 33% of asset owners report facing barriers in gaining access to investment grade corporate bond products (indices, benchmarks, funds) that align with their fixed income climate strategies.5

- Asset owners develop clarity on the purpose of their climate benchmark through internal discussions rooted in the purpose of the organisation.

- Asset owners are increasingly tailoring the implementation of their climate-related targets to the specific characteristics of the asset class, for example by not participating in corporate bond primary issuances while retaining stocks in the same company.

- As auto-allocators of capital, indices are a potentially powerful tool; however, their engagement potential is largely untested.

- There is asset owner demand for indices that focus on the real economy net zero transition.

- Asset owners are raising index standards by engaging with index providers and by developing ‘off the shelf’ indices to improve common market standards.

- Our survey and interviews identified asset owners of all sizes who have found suitable climate benchmark solutions.

For all the implementation challenges identified, practical approaches have been pioneered by peers.

Methodology

This report is based on a combination of desk-based research covering 309 asset owners, an in-depth survey with 65 asset owner respondents from the full sample of 309, and 11 semi-structured follow-up interviews with Heads of Fixed Income or equivalent. The 65 asset owners who responded to the survey had a combined USD 260 bn invested in corporate bonds, representing almost 1% of the corporate bond market globally. All asset owners in our sample had an AUM larger than USD 1 bn and were engaged in climate-related investor initiatives (e.g., CA100+ participant, NZAOA member, CRIN member). The four types of asset owners we covered differed in the average size of corporate bond holdings: endowments had an average of 3% invested in corporate bonds, pension funds 10%, city funds 12%, and insurers 37%. City funds are included as a specific class of asset owners who directly administer in-house pension funds, infrastructure funds, and other public funds. Some city pension funds are classed as pension funds, where a separate legal entity and team coordinate this activity. The full methodology is available here and the survey questions here.

Figure 1:

Our charts are interactive! Click on different sections to filter the data or move between views.

-

Corporate bonds and climate change

Corporate bonds play a crucial role in institutional investors' portfolios. Bonds represent a larger pool of capital than equity and are more likely than equities to be purchased in the primary market — i.e., the new issue market, where companies gain access to new capital.6,7 This means that bonds have a greater potential to change the cost of and access to capital, which can ultimately put pressure on firms to enact company-level changes.

Total corporate bond debt outstanding has grown from USD 21.0 tn in 2008 to USD 33.6 tn in 2023.8 In parallel, the increase in financial flows into index funds has led indices to become significant ‘auto-allocators’ of capital.9 For large institutional investors wishing to contribute to climate change mitigation and to facilitate the transition to net zero, finding index-based financial products that are compatible with the goals of the Paris Agreement is critical.

The majority of issuers in the oil and gas sector violate the International Energy Agency's Net Zero by 2050 (NZE) scenario by engaging in fossil fuel expansion; the IEA is clear that no new oil or gas capacity is needed.10,11,12,13 Investing in newly issued debt from expansionist fossil fuel companies will affect efforts to keep global temperature increases at or below 1.5°C. This includes financing fossil fuel infrastructure such as a new coal-fired power plant or oil pipeline, which risks leading to lock-in, as current infrastructure without additional abatement already exceeds the 1.5°C carbon budget.14 While 64% of new capital for oil and gas comes from bank loans, 26% comes from bonds, with equities representing just 10%.15 Yet the bulk of attention from the responsible investment industry continues to be on equity, leaving bonds neglected despite their size, growth, and impact. Over half of carbon-intensive debt will mature before 2030 and fixed income markets will need to refinance approximately USD 600 bn each year to that point.16 As Dathan and Davydenko find, “passive demand for corporate bonds affects firms’ debt financing decisions, bond contract terms, and the cost of capital”: patterns of asset allocation are significantly shaped by current fixed income indices, including for active investment.17 Existing standard indices allocate new capital in a way that reflects existing market structures as opposed to investor motivations to mitigate system-level risk both to and from their portfolios.

-

Interim net zero and fossil fuel exclusion policies in corporate bonds

There is a widespread perception that implementing climate commitments in fixed income is more challenging than in equities.18 The Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change (IIGCC) established its first working group on fixed income in December 2022, and the group noted that “stewardship and engagement have traditionally been considered the remit of shareholders,” echoing sentiment expressed by the PRI that sustainability in fixed income is “still in its infancy".19,20 However, bond investors we interviewed for this project emphasised that environmental risks have always played a part in their consideration of ‘downside’ risks: events that could affect the rating of the company or prevent the repayment of capital.

Our survey and interview data suggest that most asset owners do have a climate strategy that includes corporate bonds, but the strategy generally is not tailored to the asset class, representing a missed opportunity for additional impact.21 Climate strategies that include corporate bonds provide fertile soil from which to grow a more targeted approach that makes the best use of the impact of both bond-specific asset allocation and engagement tools.

Figure 2:

These two graphs show the breakdown, by asset owner type, of the percentage of climate commitments that apply to corporate bonds, excluding those without an asset class breakdown from the analysis. We found that most include corporate bonds in their public commitments: 70% of the 309 asset owners in our sample have either a fossil fuel exclusion commitment or a net zero interim target. Of the asset owners in our sample, 79% (46 of 58) with interim net zero targets that specify asset class coverage have included corporate bonds. Similarly, 81% of the asset owners (110 of 136) with fossil fuel-related exclusions that specify asset class coverage have included corporate bonds. Notably, there is considerable overlap, with 65% of these asset owners holding both types of climate commitment, each applying to corporate bonds.

Significant gaps and omissions remain: many asset owners do not include an asset class breakdown in their public commitments; for example, 27% of fossil fuel exclusion commitments do not specify which asset classes they cover. Among those providing an asset class breakdown, one-fifth of the asset owners have climate commitments that do not cover corporate bonds, which does not fully align with the guidance from initiatives like the NZAOA.22 Our interviews reveal that although many asset owners intend for their commitments to apply consistently across all asset classes, they often face challenges in implementing these commitments beyond public equities. As a result, some asset owners adopt a staged approach to implementing their climate commitments, tackling equities first.

Insight: Asset owners are increasingly including corporate bonds within the scope of their climate commitments.

We now explore two forms of public climate commitments used by asset owners: interim net zero targets and fossil fuel exclusions.

Interim net zero targets

We collected data on the interim net zero targets of 132 asset owners. Of these, 47% of pension funds, 35% of insurers, and 28% of endowments had interim net zero targets that included corporate bonds.

Figure 3:

Click on the legend on these graphs to filter the categories shown.

These data reveal a significant percentage of asset owners in the survey sample with interim net zero targets that include corporate bonds. They also show that 30% of asset owners have no interim net zero target, with this percentage highest for endowments, of which 50% had no interim net zero target. Additionally, 27% of all asset owners had interim net zero commitments but did not specify asset classes, illustrating the lack of detail in many of the commitments.

Overall, none of the city funds for which we obtained information have interim net zero targets that include corporate bonds. Pension funds, insurers, and endowments in the sample also show weaker coverage of corporate bonds in their interim net zero targets compared to their fossil fuel exclusion commitments, as illustrated below.

Fossil fuel exclusions

Figure 4:

68% asset owners (211 out of 309) in our sample had fossil fuel exclusion commitments.

Insight: Our data show a growing trend among asset owners to apply fossil fuel exclusions to corporate bond holdings. Notably, all asset owners who have announced fossil fuel exclusion policies since 2022 have included corporate bonds.

We observed some variation by asset owner type: 71% of pension funds apply fossil fuel exclusions to corporate bonds, compared to 87% across other asset owners in the sample. This contrasts with pension funds having the highest percentage rate of inclusion of corporate bonds within interim net zero targets. The difference may be influenced by the regulatory pressures on pension funds to set comprehensive net zero targets, as opposed to the more intense public pressure applied to city funds and endowments to divest from fossil fuels.

Granularity of fossil fuel exclusion commitments

Figure 5:

- Full: Binding commitment to divest from any fossil fuel company (thermal coal, oil, gas) across all asset classes. Includes direct ownership, shares, commingled mutual funds, corporate bonds, and any other assets.

- Partial: Binding commitment to divest from some but not all types of fossil fuel companies (thermal coal, oil, gas) or only in specific asset classes (e.g., direct investments, domestic equity).

- Coal and tar sands: Binding commitment to divest from any thermal coal and tar sands companies.

- Coal only: Binding commitment to divest from any thermal coal companies.

Should your browser shrink this Figure, please click here for the full interactive version

The granularity of fossil fuel exclusion commitments is crucial for achieving meaningful outcomes. A key finding from our study of asset owner fossil fuel exclusion policy scopes and definitions is the diversity of approaches. Our interviews reveal that many asset owners were unaware of how their approaches align with those of their peers, often implementing mandates based on advisor recommendations without scrutinising definitions.

Some exclusion criteria are more likely to introduce important loopholes in the policies. For instance, diversified companies involved in various activities can slip through revenue thresholds. One of the world’s largest coal producers, BHP Billiton, has a coal revenue share of only 5% and would, therefore, fall through the gaps of many of the commitments made by asset owners in our sample.23 Revenue criteria can also fail to pick up fossil fuel expansionists, whose actions reduce the likelihood of remaining at or below 1.5°C. A more comprehensive approach, adopted by many asset owners, combines multiple metrics, such as revenue plus power generation. Of the 80 asset owners who used revenue thresholds, 34 (43%) employed this approach.

Insight: Combining revenue thresholds with power generation metrics is the most popular approach defining fossil fuel exclusion commitments. This method prevents diversified but highly polluting fossil fuel companies from being overlooked.

-

Challenges and approaches to implementing climate benchmarks

In parallel to this report, we provide introductory information for non-experts about what benchmarks and indices are, how they are used, and how decisions to change benchmarks are made. You can find this guide here. Climate benchmarks in the corporate bond space have the potential to enable asset owners to align their capital with a net zero future economy, driving changes in the behaviour of companies whose actions undermine efforts to stay below 1.5°C. Benchmarks can do this by providing a rules-based methodology against which to undertake robust engagement and coordinating the denial of flows of new capital. In recent years, there has been substantial growth in the number of climate-related benchmarks such as the Climate Transition Benchmark (CTB) and the Paris-Aligned Benchmark (PAB), alongside the creation of custom benchmarks by individual asset owners.24 Myriad products such as index funds and ETFs have been created using these benchmarks. Between 2017-2023, assets under management using equity and fixed income net zero benchmarks increased from around USD 10.2 bn to USD 100 bn.25 However, our research indicates that many asset owners face internal barriers to adopting these benchmarks: they are sceptical about the offerings currently available, struggle to identify one that suits their specific needs, or do not have the internal capacity to create their own.

Within our sample, 54% of asset owners already had 1.5°C-aligned, fossil-free, or other sustainable corporate bond products (such as Article 9 or EU PAB), or intended to use one in the future. Use and interest vary by asset owner type.

Figure 6:

Out of 21 pension funds, 29% (6) already had a sustainable corporate bond product, with an additional 33% (7) planning to adopt one in the future. Out of 10 endowments, 20% (2) had a sustainable corporate bond product, and another 50% (5) intended to use one in the future. In contrast, none of the insurers (0 out of 7) or city funds (0 out of 3) currently had sustainable corporate bond products. Only 29% (2 insurers) planned to use one in the future, while no city funds had such plans.

Insight: 33% of asset owners report facing barriers in gaining access to investment grade corporate bond products (indices, benchmarks, funds) that align with their climate strategies.26

This section focuses on the five major barriers that asset owners faced in relation to climate benchmark selection in corporate bonds, as identified by our survey and interviews. We also provide small case studies of strategies for success.

Lack of internal clarity about the purpose of benchmarks

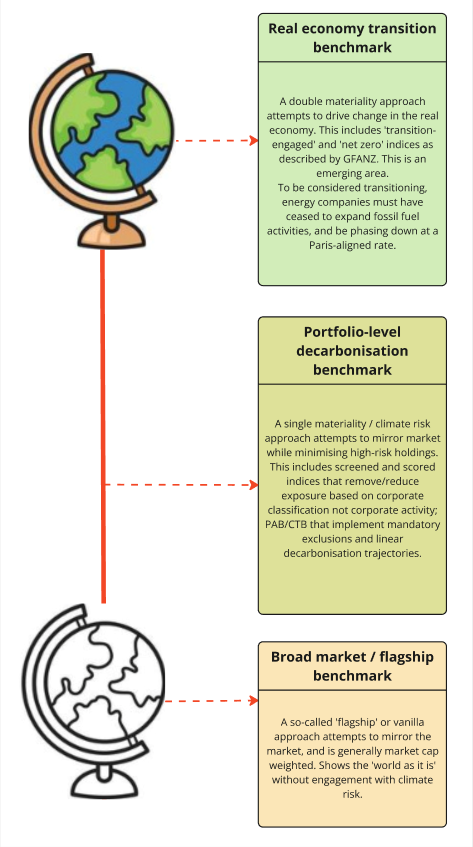

Asset owners we interviewed lacked internal clarity about the role that benchmarks played in their climate strategy and whether to synchronise approaches across asset classes. Participants expressed uncertainty about whether benchmark selection should be focused on ensuring investments align with a given climate or temperature trajectory (a ‘portfolio-level decarbonisation benchmark’, see Figure 7), or on changing the real economy to mitigate and adapt to systemic risks such as climate change (a ‘real economy transition benchmark’).27 Heads of Fixed Income described being caught between climate priorities and a tracking error budget (i.e., how much active risk they are willing or able to accept in managing their portfolio relative to a benchmark). This had, in some cases, prompted questions about a change in policy benchmark as well as portfolio-level benchmarks.

Figure 7: Different approaches to climate benchmark use

A number of participants argued that taking the same approach across different asset classes resulted in alignment and was necessary for a coherent investment strategy. Other participants favoured an approach that they felt better reflected the different characteristics and possibilities of each asset class by, for example, excluding certain companies from their debt portfolio but choosing to engage with them through their equity holdings. However these participants feared being accused of hypocrisy for treating the same company differently in different asset classes.

Internal discussions rooted in the purpose of the organisation

- Asset owners with a culture of open discussions about uncertainty and trade-offs had the greatest clarity of purpose for their benchmark implementation. This was often rooted in an acceptance that there was no ‘right answer’, and that a focus on the specific purpose of the organisation should be the priority. Asset owners who were able to state a clear and common vision across the investment team (including in relation to investment beliefs), understanding whether their benchmarks aim to contribute to changes in the real economy (i.e., impact) or to manage risk at the portfolio level, tended not to have this challenge. One asset owner relayed that the investment committee sees itself in the role of ‘productive challenger’ to the investment team’s benchmark research, working to help improve decisions. This aims to avoid situations in which there are unproductive repeated iterations of proposals.

- One mid-sized UK asset owner described their policy to “engage equity, deny debt”, aiming to stop financing companies that are not aligned with the Paris Agreement. While newly issued bonds provide fresh capital to the company, equities largely only trade in the secondary market. Therefore, they deny primary market financing by avoiding bond purchases from non-aligned companies but seek to change corporate practices through engagement where they hold equities in the same company.

- Similarly, one large North American asset owner says that “different attributes lend themselves to different procedures”: the primary role of bonds is to provide new capital to companies, whereas stocks offer an ownership stake. This provides two distinct ways of contributing to the same overarching project: conducting themselves as a universal owner. This approach is mirrored in recent academic literature.28

Insight: Asset owners develop clarity on the purpose of their climate benchmark through internal discussions rooted in the goals of the organisation.

Insight: Asset owners are increasingly tailoring the implementation of their climate-related targets to the specific characteristics of the asset class, for example by not participating in corporate bond primary issuances while retaining stocks in the same company.

Bondholder engagement is nascent, and engagement through indices is non-existent

No interviewee was able to share an example of bondholder engagement that had led to corporate behaviour change on an ESG topic. By and large, engagement activity is outsourced to external managers or to external stewardship service providers; asset owners do not have visibility on the goals, techniques or outcomes of this engagement. A number of investors across Europe and North America recognise that their debt engagement approach largely amounts to ‘piggy-backing’: adding the clout of debt assets to conversations led by equity-facing teams. Some mentioned a limited strand of bond-specific corporate engagement, for example through group investor meetings coordinated by banks, but could not point to outcomes in the real economy. Participants noted the practical challenges of standard bondholder engagement, which is tied to an issuance timeline that could be a matter of days.29

Indices can be a powerful potential lever for engagement

- Bondholders can engage company-by-company, including via their service providers, through setting and communicating guardrails that apply across a sector or theme, for example through the methodology of an index,30 or through engagement with index providers, advocating for benchmarks aligned with net zero.31

- Regarding the former, we saw some examples of bondholder-specific corporate engagement, but largely they were too nascent to demonstrate real economic impact. One medium-sized UK asset owner described having a nuanced issuer review process that they believe ensures they would not have material holdings in bonds that other asset owners would have written an exclusion policy to avoid; however, they did introduce some exclusions such as thermal coal, because “you do need to signal some sort of sentiment, or people think the worst.” Beyond this they operate an informal ‘engage and then divest debt’ strategy in the coal sector. They review a coal-dependent company’s plans, and if the phase-out approach seems reasonable, they may buy the bond initially. Following review, if they have concerns, they call the issuer to discuss. If they are unimpressed by the response at this stage, they sell.

- Examples of index-level engagement in our data were few and far between, and largely focus on process as opposed to outcomes. This is despite the fact that, according to Quigley (2023), “bondholder engagement appears to have risen up the agenda in academia, in the popular press, and among non-profits, recognising new debt issues as a critical point of intervention.”32 It seems that despite this increased awareness, index-level engagement is still in its infancy and focused on tweaks to existing processes. A large North American asset owner emphasised the importance of engaging with index providers to improve index standards. They are part of the index advisory group and complete the provider’s regular surveys with detailed feedback.

- What would a more comprehensive approach look like? There is evidence that companies threatened with exclusion from an index are more likely to change their behaviour.33 In this way, a benchmark can be seen as an engagement tool; it is a rules-based descriptor of alignment against agreed publicly disclosed criteria. Engagement using an index, for example through publishing a ‘watch list’ of companies at risk of falling afoul of the criteria and informing them of this fact, has been tested in an equities context. This has yet to be explored for fixed income. However, given the role of bonds in providing new capital to companies, there is reason to believe that the exclusion of an issuer from an index could have immediate implications for the cost of capital of a company and the volume of capital it can raise, as well as for the broader social discourse drivers of corporate behaviour change seen in equities. See Box 1 for further information.

- An index-level approach could be particularly effective in a debt context because it would provide a rules-based framework for assessing the alignment of a whole investable universe, which would avoid the practical challenges of engaging with short re/issuance timelines.

Insight: As auto-allocators of capital, indices are a potentially powerful tool; however, their engagement potential is largely untested.

Box 1: Corporate bond index with academic engagement overlay

This report has been prepared by Finance for Systemic Change, an academic centre at the University of Cambridge that has developed a research framework to build a global investment grade corporate bond index focused on mitigating emissions in the real economy alongside the protection of long-term institutional investor capital. This would be the first corporate bond index to penalise fossil fuel, electric utility, and banking and insurance issuers that directly engage in or facilitate fossil fuel expansion. This nuanced framework can help investors ‘deny debt’ to non-aligned issuers in these industries. Instead of blanket exclusion, investors have the power to reduce capital flows towards fossil fuel expansion as well as to engage with companies to change their practices.34 As bond issuers move away from fossil fuel expansion, they can re-enter the index and regain access to lower-cost capital. This re-inclusion mechanism is unique when compared to existing absolute and phased corporate exclusion approaches.35

The re-entry method aligns with academic evidence suggesting that companies threatened with exclusion from an index are more likely to change their behaviour.36 By taking an index-level and rules-based approach to corporate engagement, the project hopes to bypass the common challenges that investors face with bondholder engagement, such as short timeframes for engagement in the context of re/issuance, and practical difficulties with collaboration due to differences in investment holdings. A global Academic Board of leading experts in sustainable finance, corporate climate action, and equity and justice issues will develop and approve analysis for engaging with ‘edge cases’: companies close to aligning with or losing alignment with index rules. This enables the project team to test the efficacy of targeted evidence-driven engagement with companies facing a change in cost of capital.

There are currently limited offerings for ambitious fixed income climate benchmarks

Some asset owners feel that current benchmark offerings are insufficiently ambitious. For example, one large North American asset owner noted that no index provider had yet developed an approach for financial actors facilitating fossil fuel expansion, such as banks. Another mid-sized European asset owner noted that many of the available indices in the market looked only at corporate social responsibility (not overarching business practices), and that no existing ‘off the shelf’ indices had an approach that focused on changes in the real economy (see Figure 7).

Insight: There is asset owner demand for indices that focus on the real economy net zero transition.

Despite the dissatisfaction with existing index provider offerings, asset owners generally remained with their provider and invested against their standard base index. Considerations such as the number of bonds covered and the range of other index options available drove this decision regardless of the specific provider used, as can be seen in the graph below:

Figure 8:

Asset owners are raising standards

- We identified three asset owners in our sample (one large and one small North American asset owner, and a large European asset owner) who have worked, or are working, with index providers to create new ‘off the shelf’ indices that any asset owner can use. This includes asset owners investing in-house and using asset managers. Asset owners noticed that their needs were not fulfilled by existing offerings, and instead of developing manager-level solutions, collaborated with index providers – without retaining Intellectual Property (IP) themselves – to offer a commons-based solution. In one case, an explicit motivation was to include the infrastructure available to the market as a whole, with the awareness that asset owners are some of the only actors in the market who are not solely commercially-led entities. The large North American asset owner has decided to shift from a custom benchmark to the public benchmark they are co-developing, with the aim to aid and encourage other asset owners to adopt ambitious climate benchmarks and strategies.

Insight: Asset owners are raising index standards by engaging with index providers and by developing ‘off the shelf’ indices to improve common market standards.

Smaller asset owners find it more difficult to find climate-related products

In our sample, asset owners already using 1.5°C-aligned, fossil-free, or other sustainable corporate bond products (such as Article 9 or EU PAB) had a median AUM of USD 33 bn, compared to a median AUM of USD 7 bn for those without such products.

In interviews, asset owners across various geographies mentioned that asset managers see ESG as a way of charging clients higher fees. They were concerned about the cost of using custom or more expensive climate benchmarks, with one noting that the climate-related alternative to their base benchmark would have cost double.

75% of those who had experienced barriers in gaining access to investment grade climate-aligned corporate bond products (benchmarks or funds) invested less than 7.5% of their portfolio in corporate bonds. This can be seen in the graph below:

Figure 9:

Our survey and interviews identified asset owners of all sizes who have found suitable climate benchmark solutions

- A smaller North American asset owner in our sample received a clear organisational mandate on climate and used this to approach an index provider to create a new index with stricter environmental criteria. The index was based on standard public criteria instead of being entirely bespoke for the asset owner, which the owner saw as important in terms of avoiding a conflict of interest, and because they felt it was important for the index to be accessible to all as a common good.

- A medium-sized UK pension scheme with a younger-than-average membership base observed that while short-term scenario analyses indicate that a more orderly transition negatively affects performance, in the long term, quicker climate action is beneficial to overall portfolio performance. They consequently see their fiduciary duty as having a strong focus on real economy impacts, both in managing existing transition and physical risks around the current slow transition to net zero and in taking a long-term view of which issuances to hold. Similarly, a large North American asset owner’s asset liability management (ALM) study revealed that their liability matching obligations would be jeopardised by a failure to transition to net zero. This served as a clear directive for them to take part in the co-development of a new climate bond index.

- A medium-sized UK asset owner interviewee concluded that specialist climate benchmarks were too expensive for their limited allocation to corporate bonds. They chose to work at the asset manager level, instead of using a policy benchmark based on an index. They instruct their asset manager to implement the Climate Transition Benchmark (CTB) methodology rules and their internal exclusion list directly, instead of purchasing a benchmark. Performance is instead tracked against their manager’s standard parent index, with the CTB methodology treated as a loose target. Their asset manager now also has access to a wider range of datasets than most index providers, who primarily rely on in-house sources. Asset owners with smaller corporate bond allocations often focus on the manager instead of the index.

Implementation challenges: tracking error and data

Tracking error

‘Tracking error’ as a phrase is used differently according to context, but for the purposes of this section we take it to refer to the difference between the performance of a mandate which uses a climate-related performance benchmark, and the performance of the fund’s policy benchmark or specific mandate performance benchmark.

Some asset owner participants have immediate concerns that adopting a climate benchmark could lead to an unacceptably high tracking error, given that such benchmarks often exclude a large number of issuers. Other asset owners are concerned about the increasing misalignment between ‘the world as it is’ (the real economy) and ‘the world as it needs to be’ (the trajectory of climate benchmarks) could lead to growing tracking error. As a result, they remain hesitant to adopt ‘real economy’ benchmarks aimed at driving changes in the real economy (see Figure 7). One solution to tracking error concerns in this area is to adopt a climate benchmark as the policy benchmark.

This reflects a significant philosophical and attitudinal divergence, where some asset owners see an index as an attempt to reflect the investment universe, whereas others see it as a set of conscious (often subjective) decisions about the universe the asset owner wants to invest against. See Section ‘Lack of internal clarity about the purpose of benchmarks.’

Data quality and access

- Unintended consequences can result from gaming metrics. One medium-sized UK asset owner noted that up to ⅔ of their emissions intensity reductions are due to changes in companies’ revenues, not changes in absolute emissions. They noted the need for alternative metrics that have a meaningful impact in the real economy.

- Historical bias in the data can penalise companies for past actions rather than credit them for present or future changes. However, one asset owner noted that some integrated oil and gas companies had recently reneged on their commitments, highlighting the challenge of relying exclusively on stated future plans.

Practical approaches to benchmark implementation

Overcoming tracking error concerns

- Asset owners who had internally agreed on a level of tracking error were better able to articulate whether they wanted an index that attempted to reduce climate risk to the portfolio, (a portfolio-level decarbonisation benchmark) or an index that described changes to the investable universe that would (hopefully) trigger real-world climate outcomes (a real economy transition benchmark).37

- A small European asset owner has chosen to run two benchmarks: a climate policy benchmark and a reference benchmark. This allows them to maintain a live discussion internally about the reasons for any divergence between the two, exploring which elements may be attributed to manager performance, macroeconomic conditions, changes to systemic risks, etc.

- A large Australasian and a smaller North American asset owner have chosen to change their policy benchmark to redefine the overarching investment universe, which effectively eliminates concerns about tracking error.

- A third approach used by a mid-sized European asset owner was to internally agree to an “enhanced passive” strategy: the bonds they purchase are based on an index, but they incorporate more active management elements than a typical passive approach would, ultimately choosing a narrower subset of bonds. Given the complexity of investing against a bond index, issues with liquidity in some parts of the market, and the need for more flexibility around tracking error in the context of climate, these hybrid models are under exploration by a number of participants.

- Another approach came from a medium-sized UK asset owner, who started the process at the policy level instead of first determining which index was most appropriate. They implemented an ‘engage equity, deny debt’ policy, aiming to target corporate bonds’ flows of new capital to misaligned companies. This has led them to review their index, and also to review asset managers and explore a shift from passive to active mandates to ensure they are not hamstrung by tracking error concerns.

Overcoming data gaps

- Asset owners have overcome data access and quality challenges through a combination of (a) finding better data sources (b) accepting the quality of what is currently available. This includes:

- A large UK asset owner decided that the best way to deal with the problems associated with emissions intensity data was to clearly identify and communicate the external factors influencing their reported emission reductions, including revenue inflation, sales and purchases, and changes in interest rates.

- Instead of relying on existing data offerings, a large North American asset owner conducts their own internal analysis on sectors they believe require particular nuance, such as the European utility sector.

- Our survey data reveal that many asset owners look to data sources external to index providers and asset managers. For example, 19 asset owners use data from the Carbon Underground 200, which ranks and analyses the top 200 publicly-listed fossil fuel reserve owners.38 Another 9 asset owners use data from Urgewald, a German NGO that maintains databases of companies involved in the thermal coal value chain and the oil and gas value chain.39

- A small European asset owner has tackled data challenges by building a custom index that uses data on a company's impact on the environment and society as opposed to temperature-related data. Their approach involves two steps: excluding companies that are not compatible with sustainable development and using a custom sustainability rating to evaluate alignment with societal needs. This ensures they only invest in companies that provide societal benefits and avoid those causing social or ecological harm. They argue that this method is superior to the “best in class” approach, which might still support environmentally damaging companies as long as they outperform others in their industry.

-

Glossary of terms

Term

Acronym

Definition

1.5°C-aligned

-

1.5°C-aligned means strategies aimed at limiting global warming to 1.5°C, per the Paris Agreement.

Asset class

-

An asset class is a group of investments with similar characteristics, such as stocks, bonds, or real estate.

Asset owner

AO

An asset owner has legal ownership and control of assets and aims to increase their size, typically through investment in financial markets. They might be an individual, an endowment, pension fund, or the asset owning component of another entity such as a city or an insurer.

Asset liability management

ALM

Asset liability management is a financial strategy that balances assets and liabilities to manage financial risk.

Assets under management

AUM

Assets under management refers to the total market value of investments managed by a financial institution or individual on behalf of clients.

Benchmark

A reference point, like an index, used to compare the performance of a financial instrument or portfolio. See our Benchmarks Guide for more details.

Bond issuer

-

A bond issuer is an entity that borrows money by issuing bonds, promising repayment with interest.

Charities Responsible Investment Network

CRIN

The Charities Responsible Investment Network helps charities align investments with ethical, environmental, and social responsibility principles.

Climate Action 100+

CA100+

Climate Action 100+ is an investor initiative pressuring major emitters to reduce emissions and improve climate disclosures.

Corporate bonds

-

Corporate bonds are debt securities issued by companies to raise capital, with a promise to repay investors with interest.

Exchange-Traded Fund

ETF

An Exchange-Traded Fund is an investment fund traded on stock exchanges, holding various assets like stocks or bonds.

EU Climate Transition Benchmark

EU CTB

The EU Climate Transition Benchmark guides investors in aligning portfolios with carbon reduction and climate transition goals.

EU Paris-Aligned Benchmark

EU PAB

The EU Paris-Aligned Benchmark targets investments aligned with the Paris Agreement's carbon reduction goals.

EU SFDR Article 9

Article 9

EU SFDR Article 9 targets financial products with sustainable goals, requiring full disclosure of their progress.

High yield

HY

High-yield bonds, also known as junk bonds, are debt securities that offer higher interest rates to compensate investors for the higher risk of default. Their ratings are BB to D (S&P/Fitch) or Ba to C (Moody’s).

Index

A collection of entities (such as securities) used to track the performance of a specific market, sector, or asset class. See our Benchmarks Guide for more details.

Index investing

-

Index investing is a strategy where investors track the performance of a market index by investing in funds that replicate its composition.

Investment grade

IG

Investment grade bonds are debt securities with low risk of default. They have a credit rating of BBB- (S&P/Fitch) or Baa3 (Moody’s) or higher.

Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change

IIGCC

The Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change (IIGCC) is a European network promoting sustainable investment to address climate change.

Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance

NZAOA

The Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance is a group of institutional investors committed to achieving net-zero carbon emissions in their investment portfolios by 2050.

Net zero target

A goal to balance emissions with carbon removal by a set date. Interim net zero target: Milestones set before the final goal.

Tracking error

The difference between a portfolio's performance and its benchmark, measuring consistency in achieving similar returns.

-

References

Calvin, K. et al., ‘IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (Eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland’, First (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 2023.

Cojoianu, T.F. et al., ‘Does the Fossil Fuel Divestment Movement Impact New Oil and Gas Fundraising?’, Journal of Economic Geography, vol 21, no. 1, 2021, pp. 141–64.

Dathan, M. and Davydenko, S., ‘Debt Issuance in the Era of Passive Investment’ SSRN Electronic Journal, 2020, https://ssrn.com/abstract=3152612, (accessed June 27, 2024).

FFI Solutions, ‘The Carbon Underground 200’, FFI Solutions, https://www.ffisolutions.com/the-carbon-underground-200-500/, (accessed June 27, 2024).

Financial Times, ‘The Passive Attack on Bond Markets’, Financial Times, https://www.ft.com/content/95f14c0a-ea56-41cf-93d4-da4c03f1a2a6, (accessed June 27, 2024).

‘Guardrails - The Shareholder Commons’. Accessed 24 September 2024. https://theshareholdercommons.com/guardrails-3/.

Index Industry association, ‘Sixth Annual Index Industry Association Benchmark Survey Reveals Continuing Record Breaking ESG Growth, Multi-Asset Expansion by Index Providers Globally - Index Industry Association’, Index Industry Association, 2022, https://www.indexindustry.org/sixth-annual-index-industry-association-benchmark-survey-reveals-continuing-record-breaking-esg-growth-multi-asset-expansion-by-index-providers-globally%ef%bf%bc/, (accessed June 27, 2024).

International Energy Agency (IEA), ‘Net Zero Roadmap: A Global Pathway to Keep the 1.5 °C Goal in Reach – Analysis’, International Energy Agency, 2023, https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-roadmap-a-global-pathway-to-keep-the-15-0c-goal-in-reach, (accessed June 27, 2024).

IPCC, ‘Global Warming of 1.5 ºC’, IPCC, 2022, https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/, (accessed June 28, 2024).

Kumar, S., A quest for sustainium (sustainability Premium): review of sustainable bonds. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal, vol 26, no. 2, 2022, pp. 1-18.

Mackenzie, C. et al., ‘Effect of FTSE4Good Index on CSR’, Corporate Governance: An International Review, vol 21, 2013, pp. 495-512.

Meng, A. et al., ‘Tracing Carbon-Intensive Debt’, LSEG, 2024. lseg.com/content/dam/lseg/en_us/documents/sustainability/tracing-carbon-intensive-debt-lseg.pdf, (accessed June 27, 2024).

OECD, ‘Global Debt Report - OECD’, OECD, 2024, https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2024/03/global-debt-report-2024_84b4c408.html, (accessed July 31, 2024).

PGIM, ‘Gatekeeper Pulse - Conditions Call for Active Solutions’, PGIM, Issue no. 4, https://www.pgim.com/ucits/getpidoc?file=2D8778E529B94181BD8D9C526989ED3B, (accessed June 27, 2024).

Principles of Responsible Investment (PRI), Guidance and case studies for ESG integration: equities and fixed income. PRI, 2018, p. 13, https://www.unpri.org/investment-tools/guidance-and-case-studies-for-esg-integration-equities-and-fixed-income/3622.article, (accessed June 29, 2024).

Quigley, E., ‘Universal Ownership in Practice: A Practical Investment Framework for Asset Owners’, SSRN Electronic Journal, 2020, https://ssrn.com/abstract=3638217, (accessed June 27, 2024).

Quigley, E., ‘Evidence-based climate impact: A financial product framework’, Energy Research & Social Science, vol 105, p. 103252, 2023.

Reclaim Finance, ‘Our Demands on Coal’, Coal Policy Tracker, Reclaim Finance, https://coalpolicytool.org/our-demands-on-coal/, (accessed June 27, 2024).

Rieneke, S. and Chapple, W., ‘Carrot and Stick? The Role of Financial Market Intermediaries in Corporate Social Performance’. Business & Society, vol 55, no. 3, 2016, pp. 398–426.

SIFMA, ‘The Capital Markets Fact Book’, SIFMA, 2024, https://www.sifma.org/resources/research/fact-book/, (accessed June 27, 2024).

The Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change (IIGCC), ‘A Critical Element: Net Zero Bondholder Stewardship Guidance – Engaging with Corporate Debt Issuers’, IIGCC, 2023, https://139838633.fs1.hubspotusercontent-eu1.net/hubfs/139838633/Past%20resource%20uploads/IIGCC-Net-Zero-Stewardship-Guidance.pdf, (accessed June 29, 2024).

The Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change (IIGCC), ‘Enhancing the Quality of Net Zero Benchmarks’, IIGCC, 2023, https://139838633.fs1.hubspotusercontent-eu1.net/hubfs/139838633/Past%20resource%20uploads/IIGCC-Enhancing-the-Quality-of-Net-Zero-Benchmarks.pdf, (accessed June 27, 2024).

The Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change (IIGCC), ‘Net Zero Investment Framework 2.0’, IIGCC, 2024, https://www.iigcc.org/hubfs/NZIF%202.0%20Report%20PDF.pdf, (accessed June 29, 2024).

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), ‘Target Setting Protocol: 2nd edition’, United Nations Environment Programme, 2022, p. 15, https://www.unepfi.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/NZAOA-Target-Setting-Protocol-Second-Edition.pdf, (accessed June 27, 2024).

Urgewald, ‘Global Oil & Gas Exit List 2023’, Urgewald, https://gogel.org/, (accessed June 27, 2024).

Urgewald, ‘Global Coal Exit List 2023’, Urgewald, https://www.coalexit.org/, (accessed June 27, 2024).

-

Endnotes

A glossary of terms can be found at the bottom of this report.

S. Kumar, A quest for sustainium (sustainability Premium): review of sustainable bonds. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal, vol 26, no. 2, 2022, pp. 1-18.

M. Dathan and S. Davydenko, ‘Debt Issuance in the Era of Passive Investment’ SSRN Electronic Journal, 2020, https://ssrn.com/abstract=3152612, (accessed June 27, 2024); S. Rieneke, and Wendy Chapple, ‘Carrot and Stick? The Role of Financial Market Intermediaries in Corporate Social Performance’. Business & Society, vol 55, no. 3, 2016, pp. 398–426.

For the purposes of this report, references to "corporate bonds" include both non-financial and financial corporate bonds, unless otherwise specified.

Investment grade is a level of credit rating for stocks or bonds regarded as carrying a low risk of default.

SIFMA, ‘The Capital Markets Fact Book’, SIFMA, 2024, https://www.sifma.org/resources/research/fact-book/, (accessed June 27, 2024).

E. Quigley, ‘Universal Ownership in Practice: A Practical Investment Framework for Asset Owners’, SSRN Electronic Journal, 2020, https://ssrn.com/abstract=3638217, (accessed June 27, 2024).

OECD, ‘Global Debt Report - OECD’, OECD, 2024, https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2024/03/global-debt-report-2024_84b4c408.html, (accessed July 31, 2024).

M. Dathan and S. Davydenko, ‘Debt Issuance in the Era of Passive Investment’ SSRN Electronic Journal, 2020, https://ssrn.com/abstract=3152612, (accessed June 27, 2024).

Urgewald, ‘Global Coal Exit List 2023’, Urgewald, https://www.coalexit.org/, (accessed June 27, 2024).

Urgewald, ‘Global Oil & Gas Exit List 2023’, Urgewald, https://gogel.org/, (accessed June 27, 2024).

International Energy Agency (IEA), ‘Net Zero Roadmap: A Global Pathway to Keep the 1.5 °C Goal in Reach – Analysis’, International Energy Agency, 2023, https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-roadmap-a-global-pathway-to-keep-the-15-0c-goal-in-reach, (accessed June 27, 2024).

IPCC, ‘Global Warming of 1.5 ºC’, IPCC, 2022, https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/, (accessed June 28, 2024).

Abatement is a contested concept; see Kate Dooley, Zebedee Nicholls, Malte Meinshausen, Carbon removals from nature restoration are no substitute for steep emission reductions, One Earth, Volume 5, Issue 7, 2022, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2590332222003232; Calel, Raphael and Colmer, Jonathan and Dechezleprêtre, Antoine and Glachant, Matthieu, Do Carbon Offsets Offset Carbon? (2021). CESifo Working Paper No. 9368 http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3950103; Anderson, K. The inconvenient truth of carbon offsets. Nature 484, 7 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/484007a; Bumpus, A.G and D. M. Liverman,. ‘Accumulation by Decarbonization and the Governance of Carbon Offsets’, Economic Geography, vol. 84, no.2, 2009, pp. 127–55 K. Calvin et al., ‘IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (Eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland’, First (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 2023.

T.F Cojoianu et al., ‘Does the Fossil Fuel Divestment Movement Impact New Oil and Gas Fundraising?’, Journal of Economic Geography, vol 21, no. 1, 2021, pp. 141–64.

A. Meng et al., ‘Tracing Carbon-Intensive Debt’, LSEG, 2024. lseg.com/content/dam/lseg/en_us/documents/sustainability/tracing-carbon-intensive-debt-lseg.pdf, (accessed June 27, 2024).

M. Dathan and S. Davydenko, ‘Debt Issuance in the Era of Passive Investment’ SSRN Electronic Journal, 2020, https://ssrn.com/abstract=3152612, (accessed June 27, 2024).

For example, see: The Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change (IIGCC), ‘Enhancing the Quality of Net Zero Benchmarks’, IIGCC, 2023, https://139838633.fs1.hubspotusercontent-eu1.net/hubfs/139838633/Past%20resource%20uploads/IIGCC-Enhancing-the-Quality-of-Net-Zero-Benchmarks.pdf, (accessed June 27, 2024).

The Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change (IIGCC), ‘A Critical Element: Net Zero Bondholder Stewardship Guidance – Engaging with Corporate Debt Issuers’, IIGCC, 2023, p. 6, https://139838633.fs1.hubspotusercontent-eu1.net/hubfs/139838633/Past%20resource%20uploads/IIGCC-Net-Zero-Stewardship-Guidance.pdf, (accessed June 29, 2024).

Principles of Responsible Investment (PRI), ‘Guidance and case studies for ESG integration: equities and fixed income’, PRI, 2018, p. 13, https://www.unpri.org/investment-tools/guidance-and-case-studies-for-esg-integration-equities-and-fixed-income/3622.article, (accessed June 29, 2024).

E. Quigley, ‘Evidence-based climate impact: A financial product framework’, Energy Research & Social Science, vol 105, p. 103252, 2023.

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), ‘Target Setting Protocol: 2nd edition’, United Nations Environment Programme, 2022, p. 15, https://www.unepfi.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/NZAOA-Target-Setting-Protocol-Second-Edition.pdf, (accessed June 27, 2024).

Urgewald, ‘Global Coal Exit List 2023’, Urgewald, https://www.coalexit.org/, (accessed June 27, 2024).

Index Industry association, ‘Sixth Annual Index Industry Association Benchmark Survey Reveals Continuing Record Breaking ESG Growth, Multi-Asset Expansion by Index Providers Globally - Index Industry Association’, Index Industry Association, 2022, https://www.indexindustry.org/sixth-annual-index-industry-association-benchmark-survey-reveals-continuing-record-breaking-esg-growth-multi-asset-expansion-by-index-providers-globally%ef%bf%bc/, (accessed June 27, 2024).

The Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change (IIGCC), ‘Enhancing the Quality of Net Zero Benchmarks’, IIGCC, 2023, https://139838633.fs1.hubspotusercontent-eu1.net/hubfs/139838633/Past%20resource%20uploads/IIGCC-Enhancing-the-Quality-of-Net-Zero-Benchmarks.pdf, (accessed June 27, 2024).

Investment grade is a level of credit rating for stocks or bonds regarded as carrying a low risk of default.

We aim to align our terminology with: Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), ‘Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero Launches Consultation on Index Guidance to Support Real-Economy Decarbonisation’. (blog), October 2024. https://www.gfanzero.com/press/consultation-on-index-guidance/, (accessed October 10, 2024).

E. Quigley, ‘Evidence-based climate impact: A financial product framework’, Energy Research & Social Science, vol 105, p. 103252, 2023.

The Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change (IIGCC), ‘A Critical Element: Net Zero Bondholder Stewardship Guidance – Engaging with Corporate Debt Issuers’, IIGCC, 2023, https://139838633.fs1.hubspotusercontent-eu1.net/hubfs/139838633/Past%20resource%20uploads/IIGCC-Net-Zero-Stewardship-Guidance.pdf, (accessed June 29, 2024).

‘Guardrails - The Shareholder Commons’. Accessed 24 September 2024. https://theshareholdercommons.com/guardrails-3/.

The Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change (IIGCC), ‘Net Zero Investment Framework 2.0’, IIGCC, 2024, https://www.iigcc.org/hubfs/NZIF%202.0%20Report%20PDF.pdf, (accessed June 29, 2024).

Quigley, E., 2023. ‘Evidence-based climate impact: A financial product framework’. Energy Research & Social Science, vol. 105, 2023, p. 103252, ISSN 2214-6296, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2023.103252.

S. Rieneke, and W. Chapple. ‘Carrot and Stick? The Role of Financial Market Intermediaries in Corporate Social Performance’. Business & Society, vol 55, no. 3, 2016, pp. 398–426; C. Mackenzie et al., ‘Effect of FTSE4Good Index on CSR’, Corporate Governance: An International Review, vol 21, 2013, pp. 495-512.

Quigley, E., 2023. ‘Evidence-based climate impact: A financial product framework’. Energy Research & Social Science, vol. 105, 2023, p. 103252, ISSN 2214-6296, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2023.103252.

Absolute exclusion describes financial products that exclude industries such as fossil fuels on a blanket basis. Examples of phased exclusion include EU Paris Aligned Benchmark (PAB) or Climate Transition Benchmark (CTB) products.

Slager, Rieneke, and Wendy Chapple. ‘Carrot and Stick? The Role of Financial Market Intermediaries in Corporate Social Performance’. Business & Society 55, no. 3 (March 2016): 398–426. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650315575291.

We aim to align our terminology with: Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), ‘Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero Launches Consultation on Index Guidance to Support Real-Economy Decarbonisation’. (blog), October 2024. https://www.gfanzero.com/press/consultation-on-index-guidance/, (accessed October 10, 2024).

FFI Solutions, ‘The Carbon Underground 200’, FFI Solutions, https://www.ffisolutions.com/the-carbon-underground-200-500/, (accessed June 27, 2024).

Urgewald, ‘Urgewald in English’, Urgewald, https://www.urgewald.org/en/english, (Accessed July 29, 2024).

Contact Us

Learn more about our work on our website. For inquiries, contact us at bondindex@landecon.cam.ac.uk.